President Erdogan visited Athens on December 7 2017 where he shocked the Greek government by openly talking about the revision of the Treaty of Lausanne. This treaty had been signed in 1923 by Greece, Turkey, and the victorious Allies where the boundaries between the former two were finalized. Among other things, much of the Aegean sea and most of the islands came to be assigned to Greece. The Dodecanese’s islands that had been taken by Italy after 1911, came to be assigned again to Italy. Over 100 years later, Erdogan’s statement about a revision of the treaty was symptomatic of the Neo-Ottoman policy of the regime now in power in Ankara. The ideology of the AKP had been shaped by Turkish neo- Islamism and the very successful attempt by Erdogan to emasculate the Turkish military and the Turkish secular establishment by changing the constitutional structure of the Turkish state into a presidential republic and assigning overwhelming power to the presidency. The system of checks and balances that had characterized the secular constitutional order had come to an end. What is most interesting for the study of international relations of the area, is how the Islamic regime was now committed to a return to not only traditional Islamic piety, but also a more aggressive stance on foreign policy denoted by Turkish thrust into the Arab world the Balkans, North, Africa and the Persian Gulf. Above and beyond the perennial Greek-Turkish conflict over Cyprus and the control of the seabed in the Aegean, Erdogan was now committed to a reassertion of an Ottoman inspired Turkish presence in Europe, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean.

After having courted Assad’s Syria with the beginning of the so-called Arab Spring, Turkey came to support the Islamic-inspired rebels in Syria while secretly aiding and abetting the fighters of the Islamic State in Iraq, Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon. Erdogan also ditched his cooperation with Israel that had lasted for some decades and began supporting the Palestinian cause backed by practically breaking diplomatic relations with the Israeli state. The Arab Spring saw Erdogan’s regime vociferously supporting the Muslim Brotherhood and its various manifestations in the Islamic world. In its quest for Mid-Eastern hegemony, Ankara had now come to denounce Saudi Arabia and its ruling elites after the assassination of Jamal Kashoggi, a Saudi journalist who surged to celebrity because of his assassination in Turkey by Saudi agents. Turkish foreign policy also saw an ever more active influence of the Turkish government amongst Turkish immigrant populations in Western Europe and the control of mosques that had a Turkish presence in Germany, Belgium, Holland, Switzerland, and Austria. Turkish immigrants have now become a tool for an assertion of Turkish influence in the European Union as Ankara pressed for membership in the Union. Such membership was of course ever more unlikely as Europeans were growing weary of Erdogan’s truculent foreign policy.

To understand Erdogan’s worldview in terms of a reborn Neo-Ottoman political system it is useful to analyze the defeat of Turkey in the First World War. Because of the success of Ataturk in setting up a secular republic and curbing Turkish territorial ambitions, we have come to forget that the defeat of the Ottoman Empire and certainly the previous losses of Turkish-held territories in the Balkans in the 19th Century had left a traumatized Ottoman Empire in 1914. The Alliance of Turkey with Germany and Austria in the First World War had been an attempt at reconquering territories that had been lost to Balkan nationalism and European imperialism and colonialism. The defeat of Turkey and the disintegration of it control over the Arab world in 1918 had left a deep imprint on Turkish nationalist psyche. By the year 2000, Erdogan and other ideologists of the AKP were formulating an Ottoman revival focusing on the idea of getting Turkey to be a great power again. Internally it meant the creeping erosion of secularism in Turkey, the return of Koranic education, the idea of women returning to more traditional roles, and an ever more anti-Western, anti-Israeli, anti-Christian posture. With the Kashoggi affair it was pretty obvious that Turkey was trying to push Saudi Arabia into a more marginal role. It should not be forgotten that the title of the Guardian of the Two Holy Places that the Saudi King held had been originally the title of the Turkish sultan who was also the Khalif and leader of the Sunni world. The ever more strident Turkish focus on Jerusalem as an Islamic city and quasi hysterical anti-Israeli statements and of course strong pro-Palestinian Islamic sympathies amongst the Turkish population, were indicators of what I call the return of the Ottoman Empire.

Erdogan’s success owed to his ability to shape, influence, and manipulate ever larger number of the Turkish rural population with a high birth rate and migration to major urban centers where traditional rural values reasserted themselves in Islamic practices such as covering women, Koranic schools, and anti-Western, anti-Christian sentiments. In reality the real losers in Erdogan’s ascent to power were the Turkish secular elites who had come to power with the success of Ataturk’s secular republic. Islamic demographic growth had put an end to it as much as it had done anywhere else in the Islamic world. What is very revealing about Turkey is that in slightly more than 100 years, a multi-cultural multi-national state saw the disappearance of all religious minorities and Turkey became on paper a fully Sunni society. The changes in Turkish foreign policy in the last 15 years have to be seen in terms of the revival of Sunni Islam, in the confrontation between the traditional premodern world of Turksish society, in coping with the challenges of modernization and globalization, Erdogan was and is trying to bend such a reaction to his visions of a Neo-Ottoman society and state. Turkish ambitions can be seen by the ever growing presence of Turkey in Africa and Asia and of course the ethno- linguistic connection to the Turkic republics of central Asia and the Caucasus have given Erdogan an ever greater stage for neo Ottoman megalomania.

In 2016, an attempted military coup against his regime gave Erdogan the opportunity to not only destroy the political power of the armed forces that had shaped Ataturk’s state but also allowed him to compete with other radical Islamists especially those led by Fethullah Gulen, a Turkish Islamic leader who had influenced Islamic revival in Turkey since the turn of the new century. By the time he managed to change the constitution and become the supreme leader of the Turkish state with an emasculated parliament, and emasculated opposition, and an emasculated civil society, Erdogan managed to destroy all internal opposition whether secular, Islamic, or Marxist. In between he had managed to fight Kurdish separatism and begin a very aggressive foreign policy in the Aegean and the Eastern Mediterranean against Greece and Cyprus. From this last standpoint the discovery of natural gas in the Eastern Mediterranean in Cypriot territorial waters and Israeli territorial waters saw the new Ottoman state becoming ever more aggressive against Cyprus by claiming that Turkey was representing the interest of the Turkish minority, where 40% of the territory had come to be occupied by the Turkish army in 1974. By 2018, Israeli, Cypriot, and Greek agreements to build a pipeline from the Eastern Mediterranean through Greece to the Italian mainland was an ever more irritant for Ankara as it gave Greeks, Cypriots, and Israelis a strategic economic political advantage against Turkish hegemonic ambitions. Erdogan’s statement about revisiting the treaties of WWI was a harbinger of Neo-Ottoman and Islamic-tainted territorial and political ambitions. Neo-Ottoman ambitions by 2019 the configuration of power in the Middle East so the Neo-Ottoman state competing with Iran and Russia for the control of the Near East with a toothless European Union and an American administration trying to reassert American power in the wake of the rise of Russian power. Turkish hegemonic ambitions were also now coming to clash with Shi’ite Iranian attempts to control the Arab world. All this was happening while the United States was trying to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Overlapping conflicts between greater and lesser powers and the revival of radical Islam whether in its Islamic State variety, Shi’ite clericalism and the Muslim Brothers influence in the Arab world saw now an explosive mix of overlapping conflicts which render the area the most volatile and unstable region in the world. The repercussions of this conflict have to be seen in areas stretching from North Africa to West Africa, from Yemen to Kashmir, and to the cities of Europe threatened by Islamic terrorists.

Morris Mottale

Redazione

La redazione di Babilon è composta da giovani giornalisti, analisti e ricercatori attenti alle dinamiche mondiali. Il nostro obiettivo è rendere più comprensibile la geopolitica a tutti i tipi di lettori.

La crisi della democrazia negli Stati Uniti

14 Lug 2024

Che America è quella che andrà al voto il 5 novembre 2024 per eleggere il suo presidente? Chi vincerà lo scontro tra…

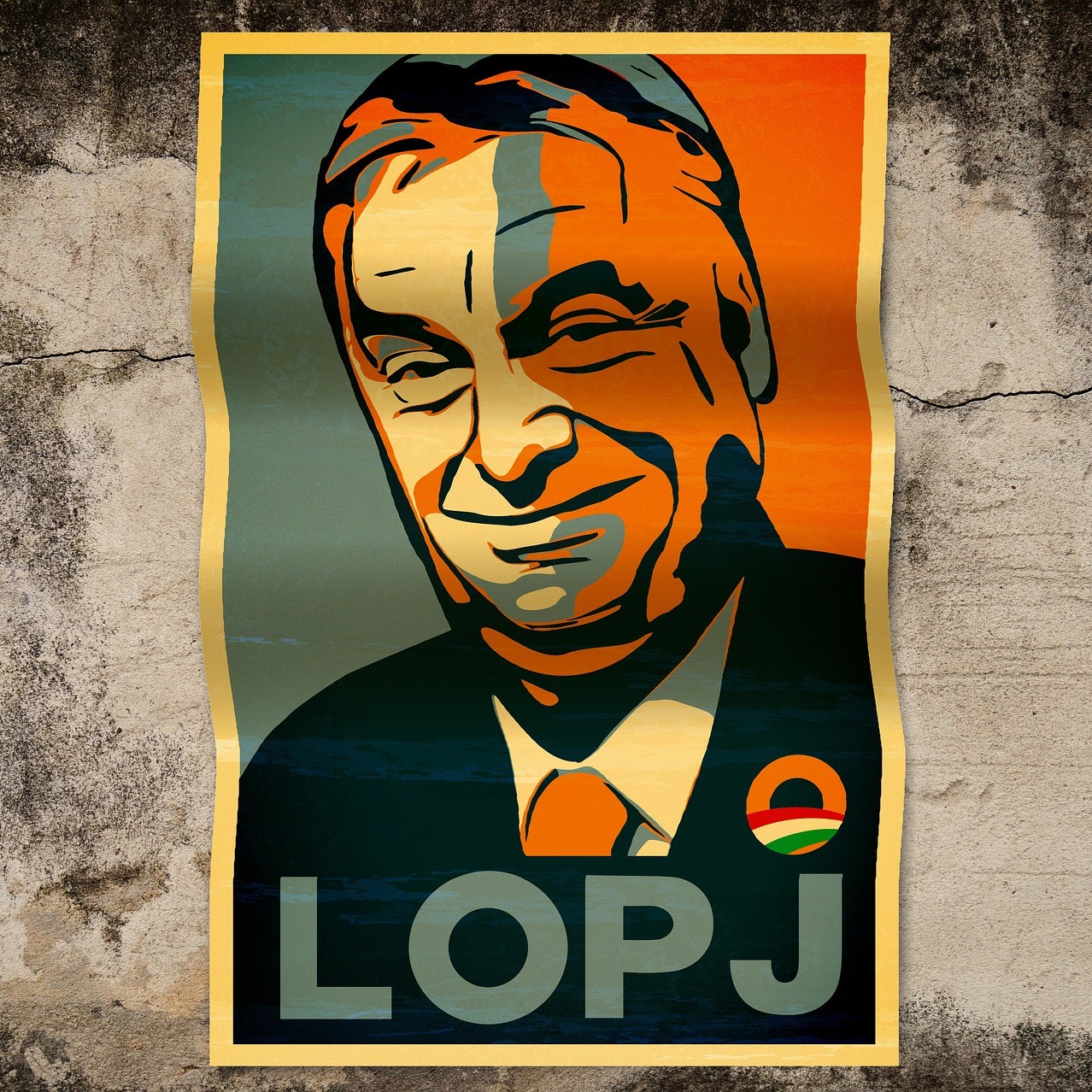

Viktor Orbán, storia di un autorevole autoritario

9 Lug 2024

Era il primo gennaio 2012 quando la nuova, e subito contestata, Costituzione ungherese entrava in vigore. I segnali di…

L’Europa e le vere sfide del nostro tempo

29 Mag 2024

Nel saggio Rompere l'assedio, in uscita il 31 maggio per Paesi Edizioni, Roberto Arditti, giornalista da oltre…

Il dilemma israeliano, tra Hamas e Iran

26 Apr 2024

Esce in libreria il 10 maggio Ottobre Nero. Il dilemma israeliano da Hamas all'Iran scritto da Stefano Piazza, esperto…