The next casualty of President Trump’s suspicion of multilateral deals could be a 30-year-old arms accord with Russia.

When Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev solemnly signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty at the White House, the leaders of the world’s superpowers hailed the transition from an era of “mounting risk of nuclear war” to one marked by the “demilitarization of human life.”

But when Donald Trump unceremoniously declared the treaty dead over the weekend, the mood was different. After taking a shot at Barack Obama for not pulling out of the agreement in response to Russian violations, the president complained about how unfair it is that Russia and China get to “do weapons” that “we’re not allowed to,” and boasted of the hundreds of billions of dollars the U.S. military could “play with” were it to build new nuclear weapons of its own. The demilitarization of human life this was not.

The Trump administration has yet to formally withdraw from the INF Treaty, but if the president makes good on his pledge, the move would be massively significant. Here’s why.

What exactly is the INF treaty?

For decades during the Cold War, the United States was obsessed with defending the homeland against the Soviet Union’s nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missiles. But by the late 1970s, it confronted a new threat from the Soviet nuclear arsenal: the deployment of shorter-range ballistic missiles capable of targeting America’s NATO allies with little advance notice.

The United States responded with what the inexorable logic of the Cold War demanded: stationing similar missiles, capable of striking the Soviet Union, in Western Europe. But it simultaneously pursued negotiations that culminated in a 1987 agreement between Reagan and Gorbachev.

The INF Treaty required the United States and the Soviet Union to permanently eliminate all ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with a range of 500 to 5,500 kilometers—the types of weapons systems, numbering in the thousands, that precipitated the showdown in Europe. In effect, it eliminated an entire class of nuclear weapons. Along with the 1991 Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, which drastically reduced the number of long-range Soviet and American nuclear weapons, it was critical in ending the nuclear-arms race.

Why has Trump decided to ditch it?

The United States and Russia have for years been trading accusations that the other party is violating the INF Treaty (Russia purportedly with a banned cruise missile; the U.S. allegedly with its missile-defense systems in eastern Europe).

But they have persisted with the agreement. Less than a year ago, the Trump administration unveiled a strategy of sticking with the INF while pressuring Russia into compliance through a mix of diplomacy, sanctions, and talk of researching and developing prohibited weapons systems of its own if necessary.

As recently as this summer, Jon Huntsman, the U.S. ambassador to Russia, was still describing the INF to reporters as “probably the most successful treaty in [the] history of arms control.”

What’s changed is that National-Security Adviser John Bolton now appears to have “the president’s ear on this issue,” Kingston Reif, the director of disarmament and threat-reduction policy at the Arms Control Association, a nonpartisan organization that seeks to raise awareness about arms-control efforts, told me.

Bolton, a proto–America Firster who joined the Trump administration in the spring, has long opposed international arms-control and nuclear-nonproliferation agreements that he claims are utterly ineffectual or intolerable infringements on the United States’ freedom of action. During the George W. Bush administration, he helped engineer the U.S. withdrawal from a treaty with Russia limiting antiballistic-missile systems and an agreement with North Korea rolling back its nuclear program, and he championed Washington’s exit from the Iran nuclear deal under Trump.

In 2011, well before the United States was calling out Russia for violating the INF, Bolton argued for either bringing new countries into the treaty or scrapping the accord entirely, since it constrained America’s ability to counter rival nuclear powers like China and nuclear aspirants like Iran and North Korea. (Even without its own intermediate-range missiles near China, Iran, and North Korea, the United States can still deter these countries with other elements of its nuclear-weapons arsenal, such as nuclear-capable aircraft and submarines.)

Richard Burt, who helped negotiate the INF Treaty during the Reagan administration, said that while he’d “love to believe that this is a very clever strategy to get leverage over the Russians” and compel them to adhere to the terms of the treaty, he seriously doubts it.

Instead, he thinks Trump’s decision is an effort to shake off restraints and assert unfettered American sovereignty—just as the administration has done by withdrawing from the Paris climate pact and trade agreements.

What happens next?

History teaches that leaders only agree to reduce their stockpiles of nuclear weapons when they improve relations with adversaries and no longer fear the types of war they once did, the nuclear-weapons expert George Perkovich once told me.

If that’s the case, however, the inverse is also true: When the ranks of adversaries swell and the specter of war looms large, nuclear buildups are a natural temptation.

Trump’s intention to quit the INF and his hesitancy to renew another Obama-era nuclear-arms-control accord with Russia are in one sense symptoms of just how fierce competition between the world’s great powers has become.

In walking away from the treaty, the president is recognizing a “changed reality” in both technological and strategic terms, Bolton declared on Tuesday during a visit to Russia.

Burt, who is now a managing partner at the firm McLarty Associates, predicted that a U.S. withdrawal from the INF Treaty would prompt Russia to again deploy intermediate-range missiles and the United States to react by rolling out new sea- and air-based weapons systems even if it doesn’t redeploy ground-based missiles to Europe. (America’s NATO allies, which might not agree to host these missiles, have so far reacted to Trump’s announcement with a mix of praise and criticism.)

Burt added that the United States and Russia are now both pouring vast sums of money into upgrading strategic bombers, land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles, submarine-launched ballistic missiles, and shiny new objects like hypersonic glide vehicles and anti-satellite systems.

“We’re in a process of sleepwalking into a new nuclear-arms race” with no restraints, Burt told me. When he served in government, in the 1980s, there was “a hypersensitivity [to] and awareness of the dangers of a nuclear conflict.” No longer.

What does all this mean for efforts to stop the spread of nuclear weapons?

When it comes to arms-control and nuclear-nonproliferation agreements, Trump has shown himself to be a consummate deal breaker. At the same time, in his pursuit of a nuclear deal with North Korea, a better nuclear deal with Iran, and now an expanded INF Treaty with Russia and China, he has yet to prove himself a deal maker.

Taken together, the moves could not just encourage an arms race among nuclear-armed states, but push other countries to consider whether they, too, want to add such weapons.

“The existing framework for nuclear control and constraints is unraveling,” Burt noted. “If the two largest nuclear powers are walking away from arms-control agreements, it provides an excuse for other countries to acquire nuclear weapons.”

“It’s easy to look back [at the Cold War] and say, ‘Gee, we avoided a nuclear conflict because we were so smart.’ I happen to think it was ‘We were very lucky,’” he continued. “And if we’re going to go through another nuclear-arms race, this time we might not be that lucky.”

Uri Friedman per The Atlantic

Redazione

La redazione di Babilon è composta da giovani giornalisti, analisti e ricercatori attenti alle dinamiche mondiali. Il nostro obiettivo è rendere più comprensibile la geopolitica a tutti i tipi di lettori.

La crisi della democrazia negli Stati Uniti

14 Lug 2024

Che America è quella che andrà al voto il 5 novembre 2024 per eleggere il suo presidente? Chi vincerà lo scontro tra…

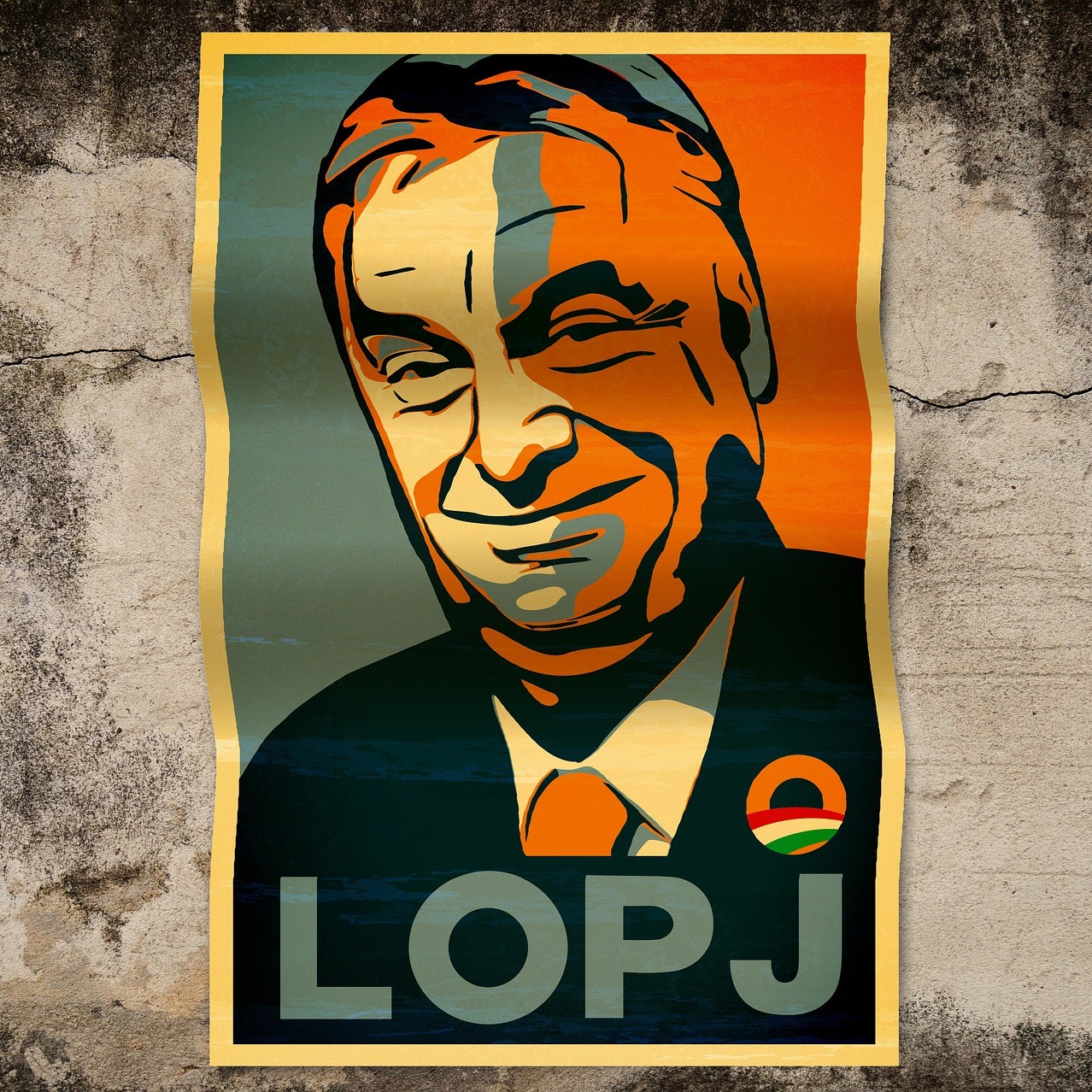

Viktor Orbán, storia di un autorevole autoritario

9 Lug 2024

Era il primo gennaio 2012 quando la nuova, e subito contestata, Costituzione ungherese entrava in vigore. I segnali di…

L’Europa e le vere sfide del nostro tempo

29 Mag 2024

Nel saggio Rompere l'assedio, in uscita il 31 maggio per Paesi Edizioni, Roberto Arditti, giornalista da oltre…

Il mondo al voto. Il futuro tra democrazie e dittature

18 Gen 2024

Il 2024 è il grande anno delle elezioni politiche nel mondo. Dopo Taiwan la Russia, l’India, il Regno Unito, l’Unione…