Sitting in a top-floor suite of his five-star hotel looking out on an ancient church dome, the self-proclaimed populist hit his talking points: The global elite is brutalising the little guy, European nations need to take back decision-making from an overbearing European Union government, and he and his new Brussels-based group, The Movement, are ready to provide polling, data analysis and messaging to help nationalist parties across Europe.

Then came an unwelcome question. “Do you actually believe in anti-fascism values?” the interviewer asked.

He sighed, not hiding his annoyance.

“We’re the anti-fascists,” he said, then proceeded to lecture the journalist, whose nation was ruled for 21 years by dictator Benito Mussolini and his National Fascist Party, on the definition of fascism.

“The problem is,” he said, “you deal in a world of no facts, OK, and all you are is spoon-fed: ‘Oh, these guys are fascists.’” He ripped “the opposition party media” and “people like yourself, sitting there sanctimoniously telling Donald Trump voters: ‘Not only is Trump a racist, but you’re a racist. Not only is Trump a fascist, but you’re a fascist.’ ”

The interview ended, a little awkwardly. The camera shut down.

Then Mr Bannon brightened immediately, shook the reporter’s hand and said: “Thanks, guys.”

Someone on the TV crew said maybe next time he could come to their studio.

“Yeah, we can do that; I’d love to do that,” Mr Bannon said, suddenly as shiny as the Roman sun beating down on his private terrace high above the Piazza del Popolo.

More than a year after being forced out as White House chief strategist, Mr Bannon, the combative former Breitbart News chief who was a key architect of President Donald Trump’s America First doctrine, has now set his sights on igniting that brand of nationalism in the rest of the world.

He argues that nationalist and populist forces, in part inspired by Mr Trump, are poised to claim political power in capitals from Pakistan to Japan to Australia, Brazil and Colombia, and he says in contact with all of them.

He says he’s going to Australia for five days in November, then Singapore over Thanksgiving, and he’s even had feelers from Israel and Egypt.

“We’re open for business,” Mr Bannon says. “We’re a populist, nationalist NGO, and we’re global.”

But first, Europe, where Mr Bannon started the week here in the Italian capital before heading to the Czech Republic, Hungary and beyond.

The globe-trotting role marks a bit of a reinvention for Mr Bannon, who months after leaving the White House in 2017 was booted from Breitbart and lost the lucrative financial backing of the billionaire Mercer family in the wake of the publication of Fire and Fury, a book that painted a grim portrait of President Trump, with Mr Bannon as a key source.

At the centre of Mr Bannon’s global efforts is The Movement, which was formed last year by Belgian right-wing politician Mischael Modrikamen, and which Mr Bannon formally joined this summer.

Mr Bannon, who earned many millions as a Goldman Sachs banker, said some of the group’s financing is coming from his own pocket – but that most of the funding will be from European donors he declines to identify.

In a series of interviews with The Washington Post, Bannon said he is trying to build The Movement into a “connective tissue” that offers nationalist and populist political parties across Europe US know-how in polling, messaging and “war-room” strategy for responding immediately to political attacks.

So far, the results have been mixed. Some on the European far right have expressed either indifference or no interest in Mr Bannon and his cause, and many establishment Europeans dismiss him as a stubble-chinned huckster who is overstating the strength of the European right.

They say he is exaggerating his ability to translate his Trump experience to the world stage, especially in Europe, where Mr Trump has disrupted long-standing alliances and is deeply unpopular.

Mr Bannon’s European critics also say he is misjudging Europe’s appetite for an American offering advice to a diverse constellation of parties that have deep historical and political differences. His arrival in Europe on Friday sparked immediate reaction.

Antonio Tajani, president of the European Parliament, said at an Italian political conference: “Dear Mr. Bannon, Go home. If you want to be a tourist, be a tourist. It’s better for you to keep quiet.”

At the same event, another European Parliament leader, Antonio Lopez-Isturiz, called Mr Bannon “a dangerous extremist” and a “disgraced ideologue” trying to destroy the European Union with “cheap nationalism.”

Mr Bannon also provoked response in the Italian press.

“When sovereignists let themselves be manoeuvred from abroad,” read a headline Monday in Il Giornale, a conservative newspaper, on a story raising scepticism about Italian parties signing up with Mr Bannon.

At the other end of the political spectrum, the self-described “communist daily” Il Manifesto blasted Mr Bannon’s ideas about Europe as “a simplistic rereading of human society and of the last ten years of globalisation.”

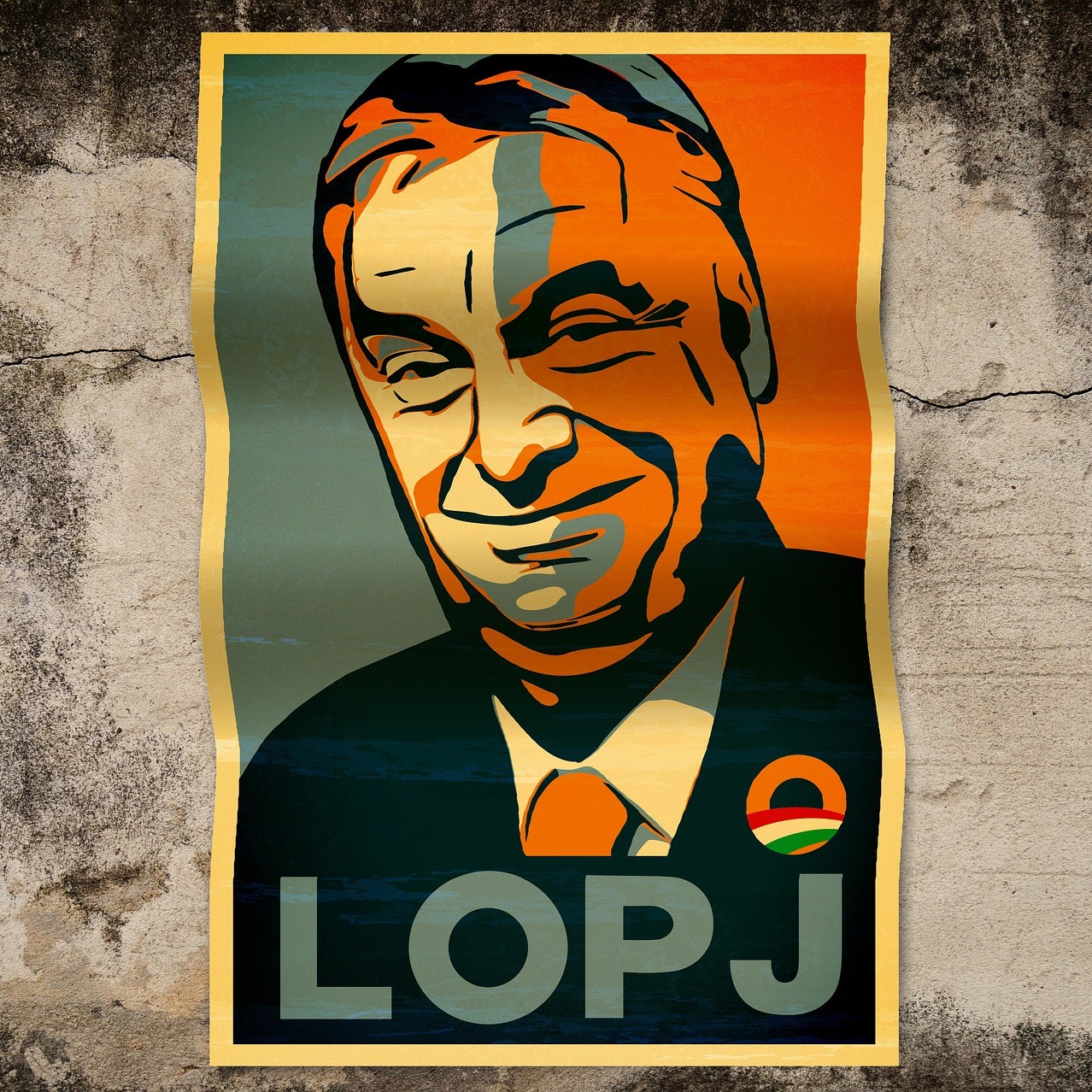

But Mr Bannon has won high-profile endorsements from far-right political leaders – most notably Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban.

In Italy, Interior Minister Matteo Salvini, the highest-profile politician in new left-right coalition government, has also pledged to support The Movement.

Mr Salvini is a hero to his followers for his aggressive crackdown on immigration, which his critics call needlessly brutal. Mr Bannon has praised Salvini for being “Italy’s version of Trump.”

Mr Bannon says that the unusual coalition-of-extremes government in Italy shows that populists and nationalists on the left and the right can put aside old dogma and govern together against immigration, for strong borders and in the economic interests of middle-class and working-class people.

“If it works here, the revolution will spread,” he says.

As he did in the Italian TV interview, Mr Bannon has run up against questions about fascism in a nation with painful memories of it.

The questions are mainly about whether nationalism and populism, if unchecked, can lead to authoritarianism and suppression of political opposition.

In one of Mr Bannon’s many interviews here, Lucia Annunziata, executive editor of the Italian HuffPost, asked him whether Mr Orban, who has been harshly criticised by European officials who say he is eroding judicial independence and free speech and growing corruption in Hungary, is a fascist.

“No, absolutely not,” Mr Bannon said. “I think Orban represents what all of these parties represent: the defence of one’s own country. Orban is a man who loves his country, a patriot, a man who puts Hungary first.”

Mr Bannon has also created a nonprofit agency, Citizens of the American Republic, to boost Republican candidates in the midterm elections in November. But after that, he says, he’ll spend most of his time in Europe until key European Parliament elections in May 2019.

Mr Bannon says neither he nor The Movement would presume to choose candidates or offer campaign strategy or funding. He simply wants to provide services that he believes can help populist and nationalist parties organise, grow, win elections and ultimately restructure the European Union into a confederation of stronger states with less intrusive regulation from Brussels.

“I’m not here to tell Europeans what to do,” he said.

He’s planning an EU-wide poll of voter attitudes about European governance and other key issues, which he says will be overseen by veteran US pollsters John McLaughlin and Pat Caddell.

Mr Bannon said he expects The Movement’s efforts between now and May to cost $25m (£19m) to $50m (£38m).

Two months short of his 65th birthday, Mr Bannon is evangelising for his nationalist vision across Europe with ferocious energy, lots of espresso and little sleep.

He uses his big, unpredictable personality as a tool for showmanship and communication. He shifts his public persona dramatically – sometimes with jarring speed. He can be a genial and famously scruffy salesman, spinning folksy tales about how his dad and granddad were phone company linemen.

Then moments later he’s a dark doomsayer, telling millennials in a speech to ultraconservative activists here that they are “modern-day Russian serfs” who will always be “two paychecks away from absolute financial ruin,” and warning of elites with control of artificial intelligence and genetic engineering who will “redefine what a homo sapien is” and lead to the “ultimate destruction of the human race.”

He constantly trashes the media and accuses them of being part of the “Party of Davos,” his go-to shorthand for out-of-touch global elites. But he cultivates media attention to spread his gospel of “economic nationalism.”

He lines up interviews with journalists like bowling pins from morning until late at night. With reporters, he can be gracious, funny, self-deprecating and likeable – until something sets him off.

Early on Sunday in Rome, Mr Bannon, who is a devout Catholic, banned The Washington Post from accompanying him on a trip he was making that day to Prague and Budapest after expressing anger that one of the newspaper’s photographer took a picture of him attending morning Mass.

Mr Bannon’s European travels, which take place aboard a leased private plane, have the feel of a political campaign in the final weeks of an election.

He is surrounded at almost all times by an entourage of friends and aides: Mr Modrikamen, the Belgian politician who founded The Movement last year; Raheem Kassam, the former head of Breitbart in London; Dan Fleuette, who has been Mr Bannon’s friend and film producer for 15 years; Benjamin Harnwell, founder of the Institute for Human Dignity, a conservative advocacy group based in Rome; Federico Arata, a former Credit-Suisse banker and writer with strong ties in Italian politics and business; Sean Bannon, the son of Mr Bannon’s younger brother; and a stocky personal bodyguard who used to be in the British Army. An independent documentary filmmaker also follows Mr Bannon everywhere.

His crew acts as his road family – as security, schedulers and advisers on everything from how to contact Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan to the best backdrop for video interviews.

On Saturday, Mr Bannon wanted context for a bit of Roman history, so he turned to Mr Kassam and Mr Harnell for help.

Mr Bannon then booted the entourage out of the suite so he could work on a speech he would deliver that night at an annual conference of Italian right-wing party activists.

A couple of hours later, everyone piled into a black Mercedes van and sedan for the ride across town to Isola Tiberina, an island in the Tiber River, where the conference was taking place next to the stone walls of a 10th-century basilica.

Mr Bannon arrived like a right-wing rock star into a huge gaggle of jostling photographers.

With police officers, private security guards and his own bodyguard leading the way, Mr Bannon waded into the scrum carrying a thin can of Red Bull.

He walked down a long flight of steps to the conference site and was led first into a small private tent for a meeting with Giorgia Meloni, leader of the right-wing Brothers of Italy party, which was hosting the event and has joined The Movement.

With late-afternoon temperatures still close to 90 degrees, Mr Bannon and Mr Meloni sat in white leather chairs and chatted about Italy’s coalition government and their shared distaste for French President Emmanuel Macron.

Photographers stuck cameras through the tall shrubs set up to protect their privacy, while Mr Bannon’s aides tried to block their view. Mr Kassam gently interrupted and handed Bannon an orange notebook asking for an autograph for someone who was waiting outside.

“MAGA!!!” Mr Bannon wrote, a reference to Trump’s “Make America Great Again” slogan, and signed his name.

Mr Bannon stood, took a sip of espresso, and the security bubble formed around him again as he made his way across a packed courtyard to the main stage, where people wore T-shirts that said, “People not Elites,” or “Patriot.”

In a tent filled to standing-room, several hundred people cheered as Mr Bannon climbed to the stage and picked up a wireless microphone.

He fixed the audience with a hard stare. His jaw muscles were visibly clenching. And he launched into a speech that sounded a lot like a Trump rally speech, tailored for an Italian audience.

He hammered all his favourite phrases and themes: Party of Davos. Corporatist elites. Central bankers. The people who preach that “You’re all racists and xenophobes and nativists.” The same ones who caused the 2008 financial crisis, then bailed themselves out at the expense of the working class.

Big applause.

Mr Bannon was getting warmed up, pacing the stage.

“You are the backbone of society. You are the glue,” he told them. “The scientific, managerial, engineering, financial, cultural elite detests you and everything you stand for,” he warned. “And they will stop at nothing, including targeting and destroying your leaders, and including coming after you.”

The crowd loved it.

One attendee, who asked not to be identified, said it was no surprise that Mr Bannon was beloved at a conference of far-right activists. “It’s like you ask people to a party and then ask if they like you,” she said.

Mr Bannon took questions, then was whisked back into the security bubble to sit for another Italian TV interview, then another half-hour of questions from a couple of dozen English-language reporters.

Mr Kassam, emceeing the questioning, said the first question would go to CNN.

“Let’s start with the haters!” Bannon said, with a big smile toward the CNN reporter. He was clearly making a joke. But moments later he was back to bashing the “opposition party media.”

Afterward, the police and security guards led Bannon and his crew back to the waiting Mercedes, still surrounded by cameras.

It was 8:30pm Mr Bannon had been on the go since before dawn.

Now he had three more media interviews scheduled back at the hotel.

Then the next morning, the Bannon entourage would head for the airport. On the schedule: a private jet to Prague for meetings, then on to Budapest for meetings over dinner, then back to Rome after midnight.

Articolo pubblicato su The Independent

Redazione

La redazione di Babilon è composta da giovani giornalisti, analisti e ricercatori attenti alle dinamiche mondiali. Il nostro obiettivo è rendere più comprensibile la geopolitica a tutti i tipi di lettori.

La crisi della democrazia negli Stati Uniti

14 Lug 2024

Che America è quella che andrà al voto il 5 novembre 2024 per eleggere il suo presidente? Chi vincerà lo scontro tra…

Viktor Orbán, storia di un autorevole autoritario

9 Lug 2024

Era il primo gennaio 2012 quando la nuova, e subito contestata, Costituzione ungherese entrava in vigore. I segnali di…

L’Europa e le vere sfide del nostro tempo

29 Mag 2024

Nel saggio Rompere l'assedio, in uscita il 31 maggio per Paesi Edizioni, Roberto Arditti, giornalista da oltre…

I segreti dell’attacco russo all’Ucraina

13 Mag 2024

Dal 17 maggio arriva in libreria per Paesi Edizioni "Invasione. Storia e segreti dell'attacco russo all'Ucraina", il…