Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has arrived in Riyadh with instructions to get to the bottom of a journalist’s disappearance from a Saudi consulate in Istanbul, while an outpouring of leaks from Turkish intelligence seem to point to a case of murder, perhaps orchestrated at an official level.

The U.S.-Saudi relationship was already attracting fierce criticism in some quarters because of the carnage of the war in Yemen; now the gruesome suspicions surrounding the fate of the Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, who lived in the United States and wrote for The Washington Post, have brought a bipartisan chorus demanding answers and threatening sanctions. Meanwhile, both the kingdom and, it seems, President Donald Trump are scrambling for a way out of the crisis. Trump declared Monday that King Salman had told him he knew nothing about the incident, and the president speculated that it could have been the work of “rogue” actors.

At stake is the nature of a 75-year-old relationship, launched under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, that has spanned presidencies and kingships and rested on a fundamental bargain: access to oil, and regional stability, in exchange for security guarantees. In its modern incarnation, that means the U.S. gets a stable partner in a roiled region and cooperation on counterterrorism and countering Iran. This bargain has long troubled critics of Saudi Arabia’s human-rights record. But now even traditionally sympathetic lawmakers are turning on the Saudi leadership; Senator Lindsey Graham directly accused Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of having Khashoggi murdered. All of this implicitly raises a question about the U.S.-Saudi partnership: Is it worth it?

“The relationship has always been founded on shared interests … It has never been founded on shared values. And we have no values in common,” said Bruce Riedel, a 30-year CIA veteran now at Brookings who recently wrote a book on the history of the U.S.-Saudi relationship. “They’re an absolute monarchy married to a theocracy.”

The gap in values was glaring even before Khashoggi disappeared about two weeks ago; Riedel argued it widened with the crown prince’s ascent to power, which has been accompanied by, among other things, a crackdown on internal dissent and a humanitarian disaster in Yemen alongside his promises of modernization. “That and other frictions have made the relationship quite brittle in the last five years or so,” said Riedel. “And the Khashoggi affair has now put all that fragility into public view in a very dramatic way.”

Yet the shared interests remain powerful, and have sustained the relationship through numerous crises in the past—including a 1973 oil embargo during the Arab-Israeli war and the revelation in the wake of the September 11 attacks that 15 of the 19 hijackers were Saudi. Since then, the Saudis have positioned themselves as a key ally in the fight against al-Qaeda and then ISIS (albeit too slowly for many officials and analysts), in particular when terrorists targeted the kingdom itself. The 9/11 Commission Report noted in 2004 that “cooperation had already become significant, but after the bombings in Riyadh in 2003”—in which more than 30 people died when Islamic militants attacked residential compounds in the city—“it improved much more. The Kingdom openly discussed the problem of radicalism, criticized the terrorists as religiously deviant, reduced official support for religious activity overseas, and publicized arrests.” The report added that in 2004, the Saudi ambassador to the United States called for a “jihad” against terrorists.

The period highlighted what the counterterrorism expert Daniel Byman has called in congressional testimony the “paradox” of U.S.-Saudi counterterrorism cooperation: “On the one hand, the Saudi government is a close partner of the United States on counterterrorism. On the other hand, Saudi support for an array of preachers and nongovernment organizations contributes to an overall climate of radicalization, making it far harder to counter violent extremism.”

“The Saudis were undergoing a period of significant domestic threat,” said Frances Townsend, who was assistant to President George W. Bush for homeland security and counterterrorism from 2004 to 2008. “[They] began to work and develop a much deeper, closer relationship with our intelligence and law-enforcement communities, including the Treasury Department. We pushed them very hard on combating financial support for terrorism. And there were tremendous gains made.”

By 2006, Saudi Arabia had largely contained its own terrorism problem—at times using methods that highlighted the difference between American interests in counterterrorism and values of rule of law, including arbitrary detention and torture, as Amnesty International detailed in a 2011 report. The success of day-to-day counterterrorism cooperation between the United States and the kingdom (which consists, among other things, of intelligence sharing about threats as well as training, countering terrorist financing, and Saudi funding for efforts like the counter-ISIS campaign in Syria) is difficult to measure, though former national-security officials from the Bush, Obama, and Trump administrations told me it was useful. “They gained tremendous experience and capability,” said Townsend.

The most notable public evidence of a payoff was when, as Riedel has detailed, then-Crown Prince Mohammed bin Nayef tipped off U.S. officials in 2010 that al-Qaeda had smuggled bombs into printer cartridges on UPS and FedEx planes already in flight, disrupting the plot. In another high-profile instance, The Washington Post reported (though the administration has never confirmed) that the CIA began operating a drone base in Saudi Arabia around 2011 to target Yemen’s al-Qaeda affiliate, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula; the newspaper said that the drone mission flown to kill the American-born radical cleric Anwar al-Awlaki was flown in part from that base.

Yet Obama was famously skeptical of what the Saudis brought to the table—at one point before becoming president labeling the Saudis “so-called allies,” and as president telling The Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg that Saudi Arabia needed to “share” the region with its archrival, Iran. But the Trump administration, according to Riedel, made Saudi Arabia the cornerstone of its regional strategy. Bob Woodward recounts in his book Fear that it was Trump’s son-in-law and adviser Jared Kushner who encouraged the president to bet big on the young crown prince, though this wasn’t an unusual affinity in Washington at the time; Mohammed bin Salman’s reformist drive looked promising to many, and he got approving headlines for his economic vision and his decision to lift the driving ban on women in the kingdom.

“I think all of us were very optimistic on the president’s first trip,” said Christopher Costa, who previously served as senior director for counterterrorism on Trump’s National Security Council and is now the executive director of the International Spy Museum. “My focus was narrowly on counterterrorism, and it was very promising … I was very optimistic, but I took a wait-and-see attitude with the Saudis.”

As more time passes, it looks more doubtful that Khashoggi will reappear. Yet at the same time it looks more likely that the U.S. and Saudi Arabia will avoid a major rupture in their relationship. But that doesn’t mean the Khashoggi affair won’t harm the relationship in subtler ways. Michael Hayden, who served as CIA director from 2006 to 2009, noted that U.S. intelligence sharing is bound by U.S. law. “If you think the Saudis are going to put your information to a use you could never do, you’re not allowed to give it to them,” he told me. “If … you have information on somebody you’re interested in, too, but you have reason to believe if you told the Saudis what his route of travel was, they’d go kill him—if you didn’t have the authority to kill him, you couldn’t tell the Saudis where he was. And so the more they act in a way that’s inconsistent with our policy and law and approaches, the more our intelligence sharing with them has to be constrained.”

The fundamental bargain, however, remains in place, even as the relationship has grown more complex. As Riedel has pointed out, even though the U.S. has reduced its own Saudi oil imports, the global economy depends on stability in the oil markets that Saudi Arabia, as one of the world’s largest oil producers, could crater on its own. “If Saudi oil exports came off the markets, the global economy would collapse,” Riedel said.

“This is not the relationship of the ’70s and ’80s, where it was really all about oil,” Townsend said. It’s much deeper and more complicated than that. But the Khashoggi incident is an inflection point, she said. “It is so shocking to our sensibilities that there’s a recognition we can’t treat human rights generally as an entirely separate issue. It has to be a considered part of the entire portfolio. I think the lesson here is, when it is not treated as a considered part of the portfolio of issues in a bilateral relationship, it may not get due weight and reference that it deserves.”

Kathy Gilsinan

articolo pubblicato su The Atlantic

Redazione

La redazione di Babilon è composta da giovani giornalisti, analisti e ricercatori attenti alle dinamiche mondiali. Il nostro obiettivo è rendere più comprensibile la geopolitica a tutti i tipi di lettori.

La crisi della democrazia negli Stati Uniti

14 Lug 2024

Che America è quella che andrà al voto il 5 novembre 2024 per eleggere il suo presidente? Chi vincerà lo scontro tra…

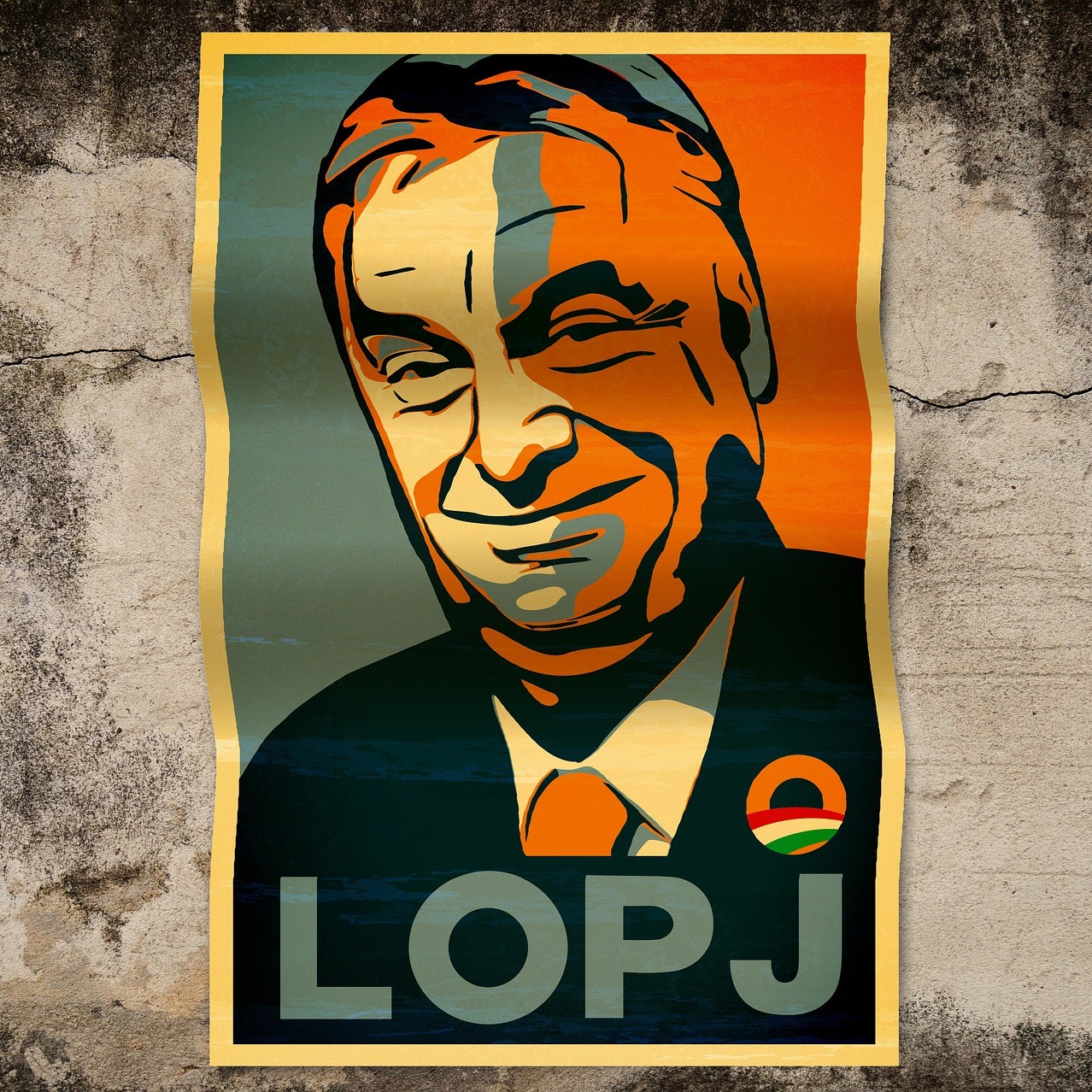

Viktor Orbán, storia di un autorevole autoritario

9 Lug 2024

Era il primo gennaio 2012 quando la nuova, e subito contestata, Costituzione ungherese entrava in vigore. I segnali di…

L’Europa e le vere sfide del nostro tempo

29 Mag 2024

Nel saggio Rompere l'assedio, in uscita il 31 maggio per Paesi Edizioni, Roberto Arditti, giornalista da oltre…

Il dilemma israeliano, tra Hamas e Iran

26 Apr 2024

Esce in libreria il 10 maggio Ottobre Nero. Il dilemma israeliano da Hamas all'Iran scritto da Stefano Piazza, esperto…