Decision to lease parts of Latakia to Iran puts Iranian personnel close to Russian installations

When Russia was invited to set up a fortified base in Hmeimim, in Syria’s coastal province of Latakia, and another in the port city of Tartus, it was under the assumption it would have the sole foreign military presence along Syria’s Mediterranean coast.

The Hmeimim tenure was open-ended, while the use of Tartus naval facility was granted until 2065 and renewable by mutual consent. However, from next October the Russians will no longer have the neighborhood to themselves – as Iran has leased parts of the port of Latakia. Iran’s arrival on the scene raises serious political and security concerns for Moscow.

The lease of Latakia will not only end Russia’s exclusive presence in the coastal district, it may also put Russian troops and military vehicles at risk. Hmeimim was subjected to a series of drone attacks between January and October of 2018 and having the Iranians so close would create a higher risk of similar operations in the area, whether by Israel, the United States, or other players on the Syrian battlefield seeking to settle old scores with the Iranians.

A permanent Iranian presence in Latakia could limit and possibly obstruct Russian surveillance and intelligence gathering, jam their radio-electronic technology, and jeopardize Russian air-defenses, aircraft, and the lives of military personnel.

Iranian request

The Syrian move comes in response to an official Iranian request, presented to Damascus last February. Realizing that they were unable to establish a permanent military presence like that of the Russians, or to illegally grab territory like the Turks, the Iranians settled for long-term economic influence in Syria in order to maintain a foothold in a crucial part of the region.

Iran gave the Syrians a line of credit totaling $6.6 billion since 2011, and that was topped up with an additional $1 billion in 2017. However, over the past three months, relations between the two countries have become even warmer, especially after President Bashar al-Assad landed in Tehran in February to meet with President Hassan Rouhani and Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei.

The two governments agreed to establish a joint chamber of commerce, a joint bank, and a power station in Latakia. Iranian developers were also given the rights to construct a 200,000-apartment housing development near the Syrian capital.

Iran has also promised to address Syria’s ongoing crippling fuel shortage by sending all future shipments of heating fuel, cooking fuel, and gasoline to the Iranian-leased section of Latakia, once it is fully operational next autumn.

Mediterranean access

For Tehran, which is suffering under crippling US sanctions, a long-sought Mediterranean foothold is a potential game-changer. “Everyone wants a Silk Road nowadays, and ports are a good place to start,” said Oklahoma University Professor Joshua Landis, speaking to Asia Times.

“Iran dreams of building a strong regional economy based on trade, highways and pipelines that cross from Iran to the Mediterranean. Helping to build up Syrian ports is only one element in a much larger vision of prosperity and shared interests. Most important will be the day that Iran can sell its oil and gas to Europe by transporting across Iraq and Syria,” said Landis.

In 2017, the Iranians asked for a license to obtain 1,000 hectares of land in the coastal city of Tartus, which they wanted to transform into an oil and gas port.

Because of its proximity to the Russian military base, Moscow nixed the proposal. So, Tehran set its sights on 5,000 hectares of fertile territory close to the Shiite Sayideh Zainab Shrine near Damascus International Airport, which it wanted to develop for agriculture.

Again, the Russians said no, offering instead agricultural fields in the countryside of Deir Ezzor, but they were inaccessible as they were controlled by Kurdish militants allied to the United States.

However, talks have now resumed to revive the project on agricultural land deemed acceptable by the Iranians. And, back on the table is a proposal to bring an Iranian GSM cellular telephone network to the Syrian market, a proposal that has been on hold for three years.

The Latakia port agreement gives the Islamic Republic the right to use a Syrian harbor with 23 warehouses for economic purposes only, but once in control of the premises, nothing prevents them from transforming it into a military facility.

A foothold in Latakia fulfills a decades-long Iranian dream of having direct access to the Mediterranean Sea, from where it can ship goods, arms — and political influence — to the rest of the world.

By SAMI MOUBAYED, DAMASCUS, ASIA TIMES

Redazione

La redazione di Babilon è composta da giovani giornalisti, analisti e ricercatori attenti alle dinamiche mondiali. Il nostro obiettivo è rendere più comprensibile la geopolitica a tutti i tipi di lettori.

La crisi della democrazia negli Stati Uniti

14 Lug 2024

Che America è quella che andrà al voto il 5 novembre 2024 per eleggere il suo presidente? Chi vincerà lo scontro tra…

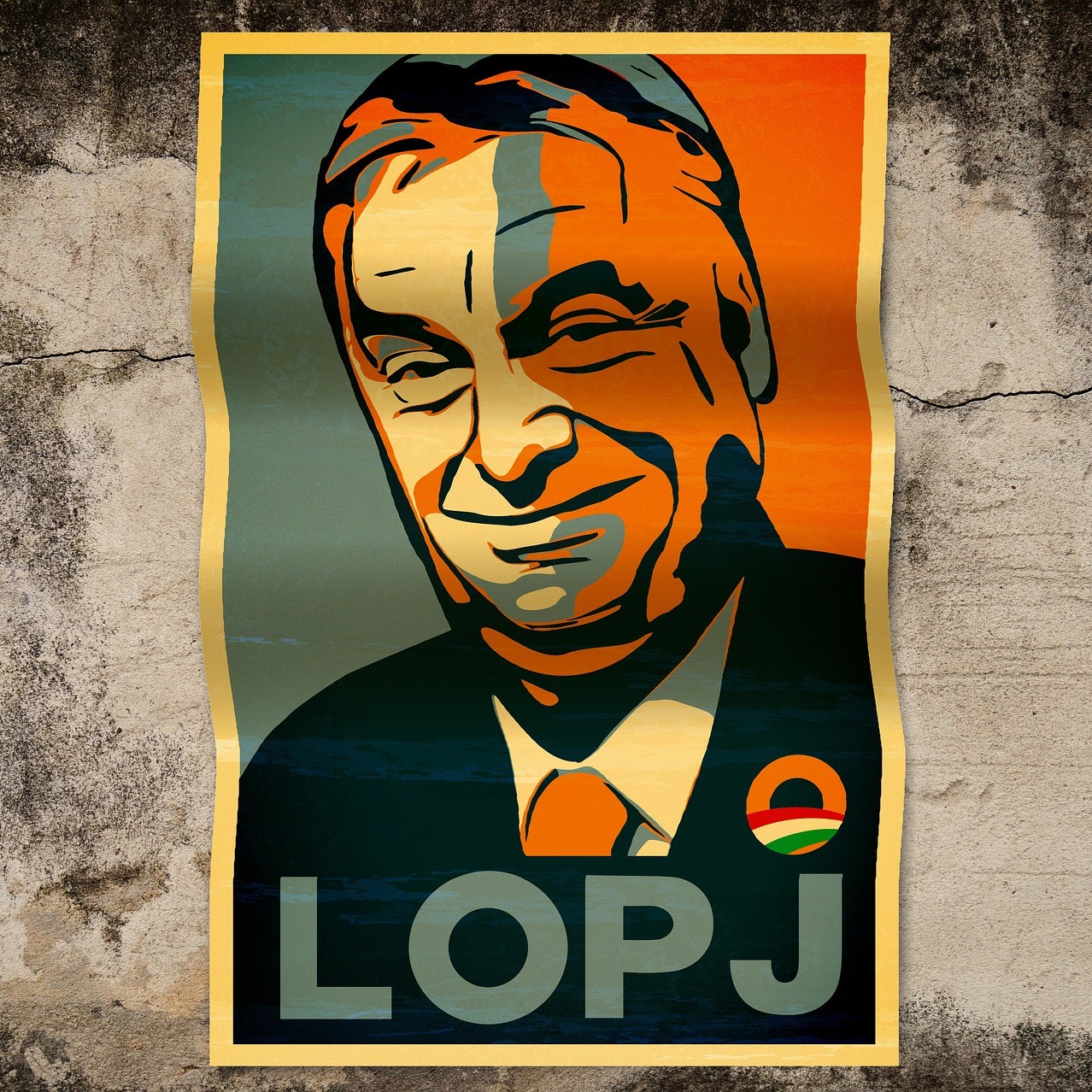

Viktor Orbán, storia di un autorevole autoritario

9 Lug 2024

Era il primo gennaio 2012 quando la nuova, e subito contestata, Costituzione ungherese entrava in vigore. I segnali di…

L’Europa e le vere sfide del nostro tempo

29 Mag 2024

Nel saggio Rompere l'assedio, in uscita il 31 maggio per Paesi Edizioni, Roberto Arditti, giornalista da oltre…

I fronti aperti di Israele in Medio Oriente

6 Nov 2023

Negli ultimi anni, sotto la guida di Benjamin Netanyahu Israele è stato molto attivo in politica estera e piuttosto…